I have been reading Robert Gerwarth’s The Vanquished on the recommendation of a friend. We had been talking about some of the reading I have done recently focused on the Caucuses and Eastern Turkey and how I had come to realise that my knowledge of what was happening in this part of the world following the end of the First World War was practically non-existent. My friend said that his outlook on much of what happened in Eastern Europe, Turkey and the Middle East, and what is currently happening in Ukraine, had been totally transformed by reading Gerwarth’s book.

I am no expert on this period and have no way of testing Gerwarth’s reading of the events. I probably need to read much more about the period to do that effectively. However, much of what he is recounting, in generally objective terms despite the horrors of the events themselves and the many hundreds of thousands of people (mostly civilians) who were killed, seems convincing and while I am sure there may be other interpretations, both of individual events and of the period as a whole, it is the scope and inclusiveness of this account that I find particularly impressive.

There are, of course, many things to learn and many things that have contemporary resonance. What it takes to lose a war. I was surprised by just how close things still were between the allies and the central powers at the end of 1918, the starvation, the despair of the troops, the gruelling horror of years of trench warfare, and yet when it came, the powers capitulated very quickly, but without troops marching across their lands. The two sides in Ukraine are nowhere near this state just now, for all the horror and all the bloodshed. Neither I would guess are ready to give in, and that might mean many more years of war, many more years of suffering.

I had not realised that the doctrine of ‘self-determination’ was effectively an invention of Woodrow Wilson, the US President who attended the peace talks in Paris. This has had a profound impact as an idea, more in the misuse, or in its failure, rather than in any positive consequences. Following the War the minority nationalities of Eastern Europe had their hopes raised and new nations were formed, mostly through the principle of self-determination. However, none of these new states were ethnically or linguistically uniform. Such mixing occurred under the older Empires that it has taken many decades to come to any kind of stability, and the problems still exist. Most of the old enemies, the central powers, were not, however, allowed self-determination and that led to resentments which built into the Second World War. The wider world, however, beyond Europe had self-determination dangled before them, but were not consider fit enough to benefit from it. The allied powers, and their leaders, particularly Wilson, were deeply racist and could not comprehend how non-Europeans could benefit from self-determination. Finally, we are now about to see, when (or if?) Putin falls, the breakup of the Russian Federation, another round of wars and coups and revolutions, initiated by the idea of self-determination

There were, of course, revolutions, coups, and civil wars in the aftermath of the Great War. Many different militias emerged, peasants, ex-soldiers, desperate aristocracies, workers, any body it seems who might have a grudge. As Gerwarth presents it, however, these groups fall into three camps: the Bolsheviks (the radical left who wanted to nationalise everything and set up workers, or peasants councils to grab land and deprive the bourgeoisie of their privilege); the right, usually referred to as ‘whites’ against the Bolshevik ‘reds’, usually nationalist, ex-military and seeking authority and stability at all costs; and finally there are the liberal democrats, but they hardly get a look in during this story. These groups, especially the left and the right, were willing to use excessive brutality and force to impose their will and incredible cruelty accompanied all the revolutions, coups, and take overs, from whichever side. I can see the collapse of the African states post-independence in much of this, the same grabs for power, the same brutality, and in Congo particularly, the same horror for year after year after year.

I was also not entirely conscious of the link between the Bolsheviks and the Jews, with many of the leaders of the soviet revolutions in Russia, Munich, Hungary and elsewhere being prominent Jews. This does not excuse the antisemitic white terrors. They brutally tortured, raped and murdered Jews wherever they could find them, often using the Bolshevik threat as an excuse, but in no way limiting themselves to Bolshevik sympathisers. At one and the same time the Jews were accused of leading a workers’ revolution and masterminding a capitalist sucking dry of the economy. As Gerwarth notes, the only common ground is the internationalism of the Jewish people over against the narrow nationalism of the right-wing militias. The horror for the Jewish people of eastern Europe had been going on for decades (and probably longer) before the Nazi final solution. I knew this, but I don’t think it had really hit home. What is probably equally horrific is that while the Bolshevik threat is probably dead, or at least sleeping for now – although the Taliban regime in Afghanistan has something of about them that seems very familiar – the right wing, popularist, nationalist threat is undoubtedly growing, and with it the horrors of antisemitism and the irrational hatred of all those who are not ‘of us’.

I think the thing that struck me most forcefully, however, was the way in which Gerwarth integrates everything together and shifts the focus of our attention. We are very used to looking at the world from the top right-hand corner of Europe, perhaps seeing France and Germany, possibly Spain, Italy and Scandinavia, but seldom very much beyond that. This is in part a legacy of the cold war, but it is also a tendency to compartmentalise the world – Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Russia, the Middle East, North Africa, the Sahel, etc. – and seeing the problems and issues within each of these, otherwise distinct, spheres. What Gerwarth does so brilliantly is to refocus our attention so much further East, and to reflect on a series of events across both Europe and North Africa which pivot around Turkey and Constantinople. On more than one occasion he suggests that the origins of the First World War occurred in the invasion of Tripoli by the Italians in 1912, followed by the Balkan wars in the next two years, some time before the assassination of the Archduke that is the official spark for the war.

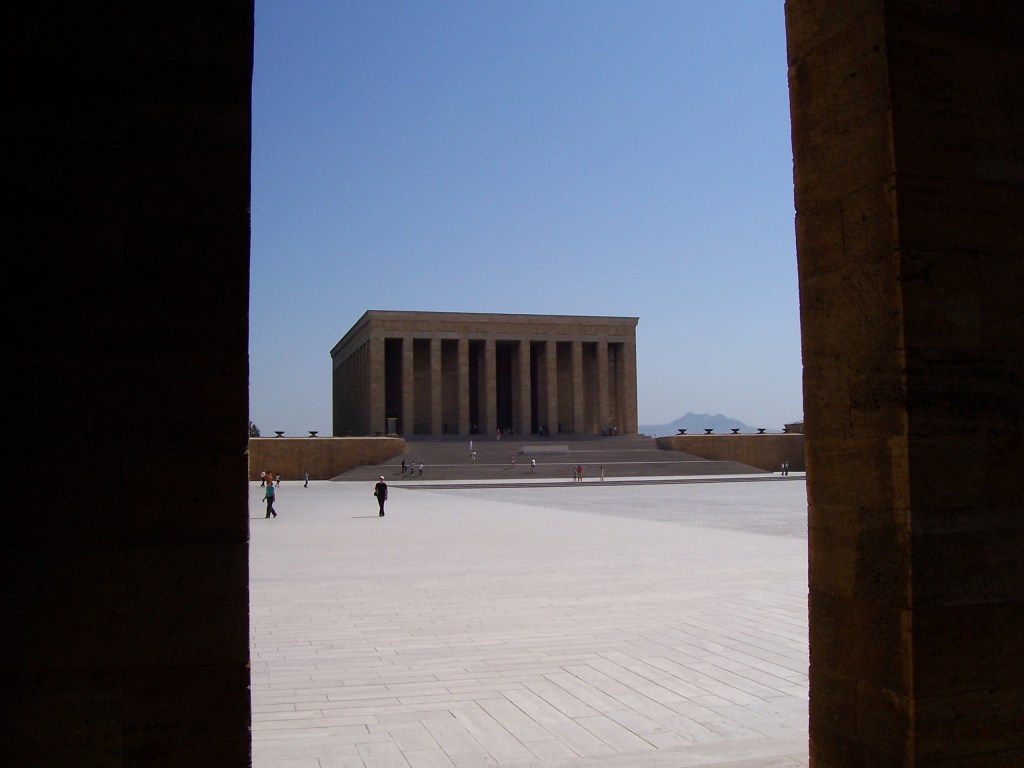

Constantinople and the Ottoman Empire had been declining for many decades, but the First World War sees this Empire collapse, like so many others across Eastern Europe and Russia. What comes next, in Europe and in the Middle East, and even across North Africa, is a consequence of that fall and the disastrous decisions of the victors, in this case Britain and France. We are still living with those consequences. We could even argue, if we draw a horseshoe around the Mediterranean, from Portugal round through Istanbul and Caucasus and on to Morocco and Senegal, that the current coups occurring across the Sahel – Mali, Niger, Chad – are part of this same series of processes. Even the presence of Wagner, supporting these coups, can be traced back to the collapse of all those Empires just over one hundred years ago.